Technology

Now Hear This

by Christopher Helman

A new ultrasound system can zap a laserlike channel of sound over hundreds

of feet to just one pair of ears in a crowd--a perfect pitch for

marketers.Elwood (Woody) Norris hangs out of a third-floor window of an office

building in New York. In his hands is his latest invention, the HyperSonic

Sound emitter. Seventy feet away, on the opposite side of Fifth Avenue,

two FORBES staffers are told to stand and listen. At first we hear only

the usual sounds of traffic, then, suddenly, the taxi honks are joined by

bird shrieks and gurgling streams of a rain forest. The jungle sounds are

so loud that, were they from a conventional loudspeaker, hundreds of

pedestrians would be able to hear them.

Remarkably, only we two can.

After a couple of steps to the right, the jungle fades out. Then Norris

pans his emitter back to us, and our heads fill with the crisp pop of a

soda can being opened and poured into a glass of ice. "Isn't that cool?"

Norris shouts. (It's his trademark phrase: "Idn'tatcool?") He grins,

revealing unnaturally white teeth. "Imagine that coming out of Coke

machines."

Coca-Cola Co. already has, along with a lengthening line of other

pitchmen. Woody Norris' HyperSonic Sound, or HSS, is about to hit the

mainstream in a very big way. He is chairman of tiny, publicly held

American Technology Corp., which has sent out HSS units for testing at

Wal-Mart and McDonald's. Sony has signed up to distribute the units in

Europe. Gateway is considering including the technology in its line of

televisions. And General Dynamics is installing them in the public address

systems of U.S. Navy ships.

Woody's biggest win -- until now, top secret -- is the coming deployment of HSS in front of as many as 100 million supermarket shoppers a week. Disney

and other big media companies plan to launch the ABC In-Store Network next

year. The venture's budget calls for some 5,600 high-end supermarkets

across 13 chains to spend $250 million installing 40,000 plasma TV screens

integrated with HSS emitters. The satellite-linked network will show news,

previews of ABC shows and Disney movies, and, of course, advertising.

Inaudible to anyone not standing in the checkout line, it wouldn't drive

cashiers batty or interfere with other store announcements.

Marketers have always dreamed of whispering into the ears of individual

shoppers as they mill around the aisles and inch along checkout lanes. But

speaker systems to date have annoyed everyone, employees especially, with

their constant, ubiquitous noise pollution. Home uses abound, too. Imagine

watching ESPN in bed at 1 a.m. without waking the wife.

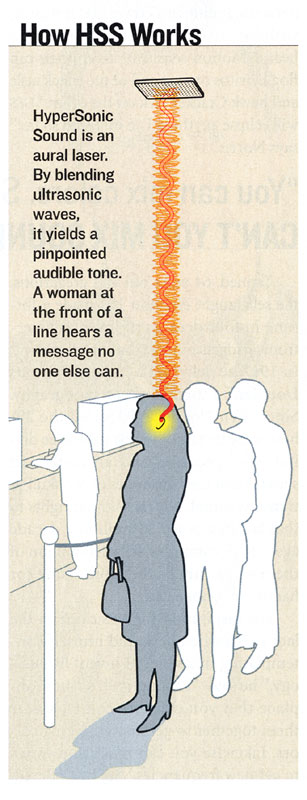

Conventional loudspeakers spew a shotgun spray of sound waves in all

directions. HSS, by contrast, shoots tightly focused waves of ultrasound

(meaning it exceeds the frequency range of human hearing). When its

various waves interact with the air, audible sounds emerge. An HSS emitter

can put a message to a single person standing in a crowd 200 feet away,

without anyone on either side able to hear it. Motion-sensitive HSS

emitters can flog Doritos on one end of the snack aisle and hawk Cracker

Jack on the other. "HSS will eclipse anything I've invented so far," says

Norris.

Tanned, 64 years old and gregarious, the self-taught engineer has made a

fortune in four decades of inventing electronic gadgets outside the

corporate tent. In 1967 he delivered a "transcutaneous Doppler," a

forerunner of sonography. Since then Norris has devised the 20-hour

cassette tape, the first palm-size digital voice recorder and an

in-the-ear speaker that uses the bones of the skull to transmit sound.

Norris sold the rights to that last device for $5 million a decade ago. GN

Netcom now sells $40 million of them a year under the Jabra name for

hands-free phone use.

His inspiration for HSS came in the late 1970s when he found himself

contemplating mixology. "I invent by analogy," he says. "I thought: ‘It's

commonplace that you can mix colors, smear them together to get new

emerging colors. Likewise you can mix radio waves to get new frequencies.'

So, I wondered, ‘Why can't you mix sound to get new sounds?'"

Norris started on HSS in earnest in 1996. He puzzled out (and only later

learned that 19th-century German engineer Heinrich Helmholtz had gotten

there before him) that when two tones are played simultaneously and loudly

enough, they interact to spawn two new tones. One carries a frequency that

is the sum of the two starting frequencies; the other is their difference.

So if you blast inaudible ultrasonic frequencies of 100 kilohertz and 101

kilohertz, you get an inaudible 201 kilohertz overtone plus an undertone

of 1 kilohertz that is well inside the range of hearing. And since

ultrasound travels in a tight line akin to laser light, the emergent tones

are audible only in a narrow, cylindrical path from source to ear.

|

|