|

Sound Technology Turns the Way You

Hear On Its Ear

By Kevin Maney

USA TODAY

SAN DIEGO Rarely is an invention so unique, so visceral and so simple that in

15 seconds most people who experience it realize it could alter everyday life.

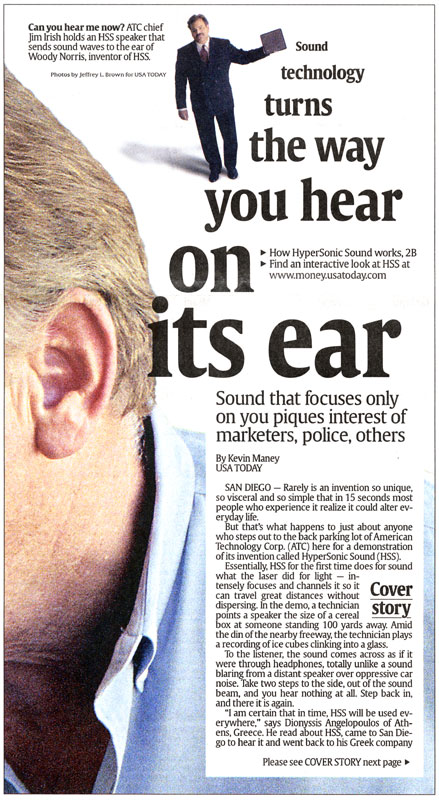

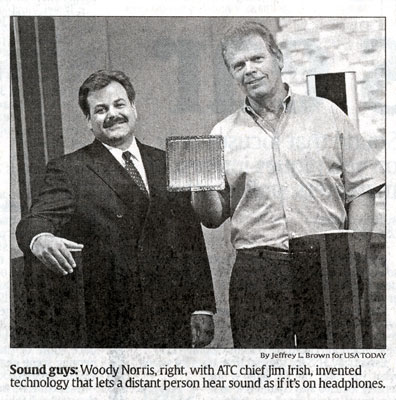

Woody Norris, inventor of ultrasound technology, holds a hypersonic sound

speaker.

But that's what happens to just about anyone who steps out to the back parking

lot of American Technology Corp. (ATC) here for a demonstration of its invention

called HyperSonic Sound (HSS).

Essentially, HSS for the first time does for sound what the laser did for light

intensely focuses and channels it so it can travel great distances without

dispersing. In the demo, a technician points a speaker the size of a cereal box

at someone standing 100 yards away. Amid the din of the nearby freeway, the

technician plays a recording of ice cubes clinking into a glass.

To the listener, the sound comes across as if it were through headphones,

totally unlike a sound blaring from a distant speaker over oppressive car noise.

Take two steps to the side, out of the sound beam, and you hear nothing at all.

Step back in, and there it is again.

"I am certain that in time, HSS will be used everywhere," says Dionyssis

Angelopoulos of Athens, Greece. He read about HSS, came to San Diego to hear it

and went back to his Greek company to build it into commercial sound systems.

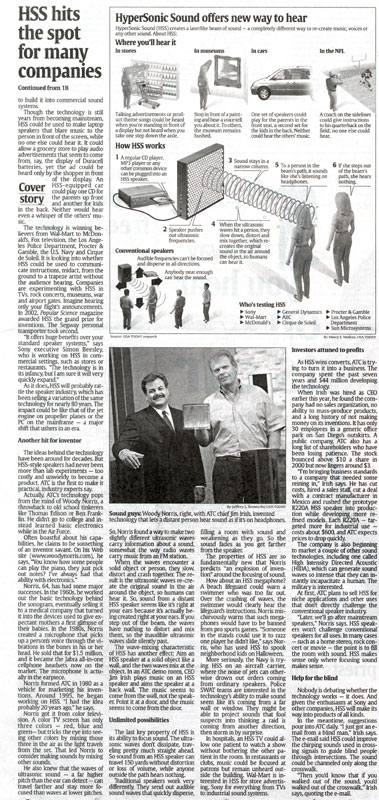

Though the technology is still years from becoming mainstream, HSS could be used

to make laptop speakers that blare music to the person in front of the screen,

while no one else could hear it. It could allow a grocery store to play audio

advertisements that seem to come from, say, the display of Duracell batteries,

yet the ad could be heard only by the shopper in front of the display. An HSS-equipped

car could play one CD for the parents up front and another for kids in the back.

Neither would hear even a whisper of the others' music.

The technology is winning believers from Wal-Mart to McDonald's, Fox television,

the Los Angeles Police Department, Procter & Gamble, the U.S. Navy and Cirque de

Soleil. It is looking into whether HSS could be used to communicate

instructions, midact, from the ground to a trapeze artist without the audience

hearing. Companies are experimenting with HSS in TVs, rock concerts, museums,

war and airport gates. Imagine hearing only your flight's announcements. In

2002, Popular Science magazine awarded HSS the grand prize for

inventions. The Segway personal transporter took second.

"It offers huge benefits over your standard speaker systems," says Sony

executive Simon Beesley, who is working on HSS in commercial settings, such as

stores or restaurants. "The technology is in its infancy, but I am sure it will

very quickly expand."

As it does, HSS will probably rattle the speaker industry, which has been

selling a variation of the same technology for nearly 80 years. The impact could

be like that of the jet engine on propeller planes or the PC on the mainframe

a major shift that ushers in an era.

Another hit for inventor

The ideas behind the technology have been around for decades. But HSS-style

speakers had never been more than lab experiments too costly and unwieldy to

become a product. ATC is the first to make it practical, industry experts say.

Actually, ATC's technology pops from the mind of Woody Norris, a throwback to

old school tinkerers like Thomas Edison or Ben Franklin. He didn't go to college

and instead learned basic electronics while in the Air Force.

Often boastful about his capabilities, he claims to be something of an inventor

savant. On his Web site (www.woodynorris.com), he says, "You know how some

people can play the piano, they just pick out notes? I've always had that

ability with electronics."

Norris, 64, has had some major successes. In the 1960s, he worked out the basic

technology behind the sonogram, eventually selling it to a medical company that

turned it into the devices used to give expectant mothers a first glimpse of

their babies. In the 1980s, Norris created a microphone that picks up a person's

voice through the vibrations in the bones in his or her head. He sold that for

$1.5 million, and it became the Jabra all-in-one cell phone headsets now on the

market. The microphone is actually in the earpiece.

Norris formed ATC in 1980 as a vehicle for marketing his inventions. Around

1995, he began working on HSS. "I had the idea probably 20 years ago," he says.

Norris got it from color television. A color TV screen has only three colors

red, blue and green but tricks the eye into seeing other colors by mixing those

three in the air as the light travels from the set. That led Norris to consider

making sounds by mixing other sounds.

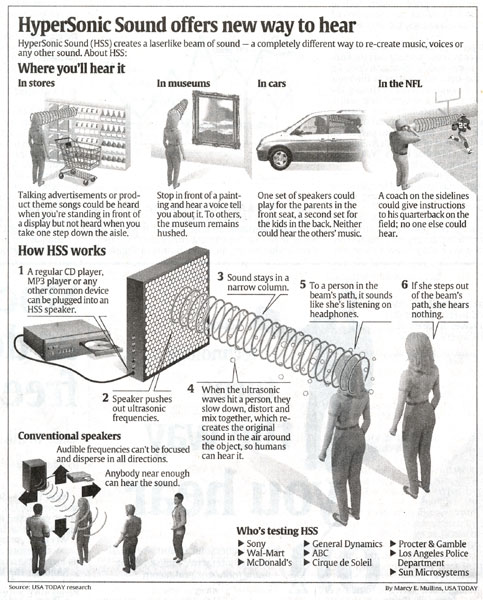

He also knew that the waves of ultrasonic sound a far higher pitch than the

ear can detect can travel farther and stay more focused than waves at lower

pitches. So, Norris found a way to make two slightly different ultrasonic waves

carry information about a sound, somewhat the way radio waves carry music from

an FM station.

When the waves encounter a solid object or person, they slow, distort and crash

together. The result is the ultrasonic waves re-create the original sound in the

air around the object, so humans can hear it. So, sound from a distant HSS

speaker seems like it's right at your ears because it's actually being created

right at your ears. If you step out of the beam, the waves have nothing to

distort and mix them, so the inaudible ultrasonic waves slide silently past.

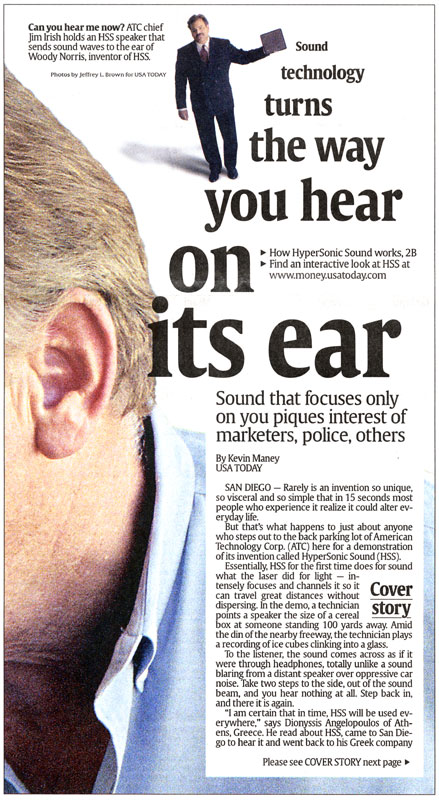

The wave-mixing characteristic of HSS has another effect: Aim an HSS speaker at

a solid object like a wall, and the two waves mix at the object. In an ATC demo

room, CEO Jim Irish plays music on an HSS speaker and aims the speaker at a back

wall. The music seems to come from the wall, not the speaker. Point it at a

door, and the music seems to come from the door.

Unlimited possibilities

The last key property of HSS is its ability to focus sound. The ultrasonic waves

don't dissipate, traveling pretty much straight ahead. So sound from an HSS

speaker can travel 150 yards without distortion or loss of volume, while anyone

outside the path hears nothing.

Traditional speakers work very differently. They send out audible sound waves

that quickly disperse, filling a room with sound and weakening as they go. So

the sound fades as you get farther from the speaker.

The properties of HSS are so fundamentally new that Norris predicts "an

explosion of invention" around the focusing of sound.

How about an HSS megaphone? A beach lifeguard could warn a swimmer who was too

far out. Over the crashing of waves, the swimmer would clearly hear the

lifeguard's instructions. Norris mischievously warns that such megaphones would

have to be banned from pro sports games. "Someone in the stands could use it to

razz one player he didn't like," says Norris, who has used HSS to spook

neighborhood kids on Halloween.

More seriously, the Navy is trying HSS on an aircraft carrier, where the noise

of jets can otherwise drown out orders coming from ordinary speakers. Police

SWAT teams are interested in the technology's ability to make sound seem like

it's coming from a far wall or window. They might be able to project sounds that

fool suspects into thinking a raid is coming from another direction, then storm

in by surprise.

In hospitals, an HSS TV could allow one patient to watch a show without

bothering the other patient in the room. In restaurants or clubs, music could be

focused at patrons but remain unheard outside the building. Wal-Mart is

interested in HSS for store advertising, Sony for everything from TVs to

industrial sound systems.

Investors attuned to profits

As HSS wins converts, ATC is trying to turn it into a business. The company

spent the past seven years and $44 million developing the technology.

When Irish was hired as CEO earlier this year, he found the company had no sales

organization, no ability to mass-produce products, and a long history of not

making money on its inventions. It has only 30 employees in a generic office

park on San Diego's outskirts. A public company, ATC also has a long list of

shareholders who have been losing patience. The stock bounced above $10 a share

in 2000 but now lingers around $3.

"I'm bringing business standards to a company that needed some reining in,"

Irish says. He has cut costs, hired a sales staff, cut a deal with a contract

manufacturer in Mexico and rushed the prototype R220A HSS speaker into

production while developing more refined models. Each R220A targeted more for

industrial use costs about $600, and ATC expects prices to drop quickly.

The company is also beginning to market a couple of other sound technologies,

including one called High Intensity Directed Acoustic (HIDA), which can generate

sound waves so intense that they can instantly incapacitate a human. The

military is interested.

At first, ATC plans to sell HSS for niche applications and other uses that don't

directly challenge the conventional speaker industry.

"Later, we'll go after mainstream speakers," Norris says. HSS speakers won't

challenge conventional speakers for all uses. In many cases such as a home

stereo, rock concert or movie the point is to fill the room with sound. HSS

makes sense only where focusing sound makes sense.

Help for the blind

Nobody is debating whether the technology works it does. And given the

enthusiasm at Sony and other companies, HSS will make its way into products of

all kinds.

In the meantime, suggestions pour into ATC daily. "I just got an e-mail from a

blind man," Irish says. The e-mail said HSS could improve the chirping sounds

used in crossing signals to guide blind people through intersections. The sound

could be channeled only along the crosswalk.

"Then you'd know that if you walked out of the sound, you'd walked out of the

crosswalk," Irish says, quoting the e-mail.

|